Blog

KISMET and CONTINGENCY --- Monaco Gallery, St. Louis, MO

Monaco is pleased to present two exhibitions opening Friday, June 26: Kismet and Contingency. Kismet opens in Monaco’s Main Gallery and features work from artists Devin Balara, Aimeé Beaubien, and CHIAOZZA. The exhibition is curated by Meghan Grubb and Jessica Hunt. The Monaco Project Gallery features Contingency, a collaborative exhibition by Meghan Grubb and Jessica Hunt. Exhibitions run through July 26. Gallery hours are 12 - 4pm every Saturday. Event information forthcoming, please check our website: monacomonaco.us, or social media: @monacomonaco for details.

KISMET Dispersed throughout a warm if somewhat bare habitat, idiosyncratic plant-like and creature-like forms playfully insinuate a post-human world that may not be so apocalyptic after all. Working with the assumption that mass extinction, inclusive of humankind, is inevitable, Kismet invites us to wander into the speculative space of what is destined to come after us, outgrowths that adapt, reorganize, and flourish on a post-anthropocene planet. The works on view form an amalgam of fragmentary, fanciful legacies of disruption and extraction, reverberations from a prior interval of time. Some things are meant to be, or so we are told.

Kismet features works from artists Devin Balara, Aimeé Beaubien, and CHIAOZZA. The exhibition is curated by Meghan Grubb and Jessica Hunt. 50% of artwork sales from Kismet will be donated to the Loveland Foundation, an organization dedicated to bringing opportunity and healing to communities of color, especially Black women and girls.

CONTINGENCY At once casually familiar and deeply unsettled, Contingency ushers the viewer into a modestly furnished dwelling-like interior space. Meticulously assembled, the room proposes a mundane sense of urgency, as if the space itself is dipped in the overlapping and perpetual sirens of a five-alarm fire, the sounds of which pulse long enough to fade to a dull background buzz in your eyes and ears. It's a state of constant stress, a world in flames, a constitutional crisis, a seedy strip club, a global pandemic, your living room.

Contingency is the product of collaboration between artists Meghan Grubb and Jessica Hunt.

50% of artwork sales from Contingency will be donated to the Loveland Foundation, an organization dedicated to bringing opportunity and healing to communities of color, especially Black women and girls.

BIOS

Devin Balara is an artist originally from Tampa, FL. She holds an MFA in Sculpture from Indiana University in Bloomington, IN and a BFA from the University of North Florida in Jacksonville, FL. She has spent the last four summers managing the metal studio at Ox- Bow School of Art in Saugatuck, MI. Devin has been a resident artist at Monson Arts in Maine, the Wassaic Project in NY (Mary Ann Unger Fellowship recipient), Vermont Studio Center (full fellowship recipient) and Elsewhere Museum in Greensboro, NC. She was the recipient of a 2014 Oustanding Student Achievement award from Sculpture Magazine. Devin has had solo exhibitions at Comfort Station in Chicago, IL, William Thomas Gallery at The University of Georgia in Athens, GA, and Ortega y Gasset Projects Skirt Space in Brooklyn, NY. Group exhibition highlights include Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, NJ, Spring Break Art Show in New York City, Torrance Shipman Gallery in Brooklyn, NY, Monaco in St. Louis, MO, The Museum of Contemporary Art in Jacksonville, FL, Goldfinch Projects in Chicago, IL, and Alone Time Gallery in New Orleans, LA.

Aimée Beaubien is an artist living and working in Chicago. Her cut-up photographic collages and photo-based installations explore collapses in time, space and place, while engaging the complexities of visual perception. Solo and two-person exhibitions include oqbo galerie, Berlin, Germany; Gallery UNO Projektraum, Berlin, Germany; Virus Art Gallery, Rome, Italy; SIM, Reykjavik, Iceland; The Pitch Project, Milwaukee, WI; BOX 13 Artspace, Houston, TX; Johalla Projects, Chicago, IL; TWIN KITTENS, Atlanta, GA; and Demo Projects, Springfield, IL. Group exhibitions include Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; Bikini Berlin, Berlin, Germany; Antenna Gallery, New Orleans, LA; Lubeznik Center for the Arts, Michigan City, IN; and UCRC Museum of Photography, Riverside, CA. Her work has been reviewed in publications such as Art in America, Art on Paper, and Art Papers. Beaubien is an Assistant Professor of Photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL where she received her MFA in 1993.

CHIAOZZA (pronounced “CHOW-zah”) is the collaborative studio of artists Adam Frezza and Terri Chiao. Based in New York City since 2011, the duo’s work explores play and craft across a range of mediums, including painted sculpture, installation, works on paper, public art, and set design. They have exhibited in solo shows at Wave Hill in The Bronx, NY; Vox Populi in Philadelphia, PA; Long Island University in Brooklyn, NY; Owen James Gallery in New York, NY; Cooler Gallery in Brooklyn, NY; CY Fiore in New York, NY; and Westchester Community College in Valhalla, NY, along with numerous group shows in the U.S. and internationally. The studio has installed public artworks in New York City and Gainesville, FL. Together, Frezza and Chiao have been artists-in-residence at Villa Lena (Tuscany, Italy), Kökarkultur (Kökar, Finland), Starry Night (Truth or Consequences, NM), The School of Making Thinking (Delancey, NY), The Lloyd Library (Cincinnati, OH), BRIC Media Arts (Brooklyn, NY), and Shell House Arts (Roxbury, NY). In 2017, they installed an acre-spanning sculpture garden with 32 large-scale works for the Coachella Arts & Music Festival in Indio, CA.

Terri Chiao (b. 1981) received a Bachelor of Arts in Art History & Architectural Studies from Brown University (’04) and a Master of Architecture from Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (’08). Before starting CHIAOZZA, she worked as a designer at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, as a designer at 2x4, and as a freelance designer focusing on small-scale architectural projects. Her work, “A Cabin in a Loft,” has been featured in numerous publications worldwide.

Adam Frezza (b. 1977) received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Studio Art at Flagler College (’01), a Post-Baccalaureate Certificate at The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (’04), and a Master of Fine Art in Drawing and Painting from University of Florida, Gainesville (’07). Since 2007, Frezza has been an independent practicing artist in New York City. He has completed artist residencies at The Corporation of Yaddo (Saratoga Springs, NY), Vermont Studio Center (Johnson, VT), and Lower East Side Printshop (NYC). His work is featured in The Viewing Program at The Drawing Center (NYC) and in New American Paintings (Issue #74).

Meghan Grubb is a visual artist based in Saint Louis, Missouri. Her practice explores a range of subjects including wilderness structures, daylight rhythms, recursive spaces, and un/natural disasters. The resulting physical work ranges from immersive installation to sculptural objects – each outcome disclosing unease between humans and the physical spaces that we inhabit. Grubb's work has been exhibited at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design (Oslo, Norway), the Wassaic Project (Wassaic, NY), Heaven Gallery (Chicago), the Pulitzer Arts Foundation (Saint Louis), and the Urban Institute for Contemporary Art (Grand Rapids, MI). She has completed residencies at Wassaic Project (NY), ACRE (Chicago), Vermont Studio Center (VT), Paul Artspace (Florissant, MO), and has received the American Scandinavian Foundation Fellowship (2012-2013), Regional Arts Commission Artists Fellowship (2015), Creative Stimulus Award (2015), Alice Cole Award (2015), recent nominations for the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors Grant (2014) and Joan Mitchell Foundation Emerging Artist Grant (2015 and 2016), and Regional Arts Commission Support Grant (2015 and 2018). Grubb is a founding member of Monaco, and received her MFA Art + Design from the University of Michigan in 2012, and her BA History + Studio Art from Wellesley College in 2005.

Jessica Lynn Hunt is a visual artist born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, where she presently resides. Her practice explores interpersonal relationships and individual experiences through the use of sculptural form, digital photography, and installation. Her research focuses on how we create, maintain, or destroy our relationships with others, and how certain experiences come to define who we are as people. Hunt received her MFA in 2018 from Southern Illinois University Edwardsville and currently teaches sculpture at John Burroughs School. She is the Assistant Director for the Bonsack Gallery in Ladue, Missouri. Hunt has exhibited work both regionally and nationally. Her public sculpture Bound is currently installed at the Scovill Sculpture Park in Illinois. Most recently, she received the Regional Arts Commission Support Grant in 2019. She is represented by Var West Gallery in Milwaukee.

Contact

info@monacomonaco.us

Location:

2701 Cherokee Street, St. Louis, Missouri 63118

Follow us:

Facebook: @monacomonaco.us

Twitter: @monacomonaco

Instagram: @monacomonaco

ART-IN-PLACE:

BOB FAUST, Michael Workman / Landing Projects. 2858 W. Belle Plaine Ave. Chicago, IL 60618 Vinyl lettering on glass, 23” h x 21” w. Not for sale. Artist’s Note: From a foundation that is at best precarious, we enter 2020 with an uncertainty that requires our own power and focus to remain upright. The number “2020” is both a date focused on this political moment in time, as well as a measurement as a call for clarity of vision. By siting “Hope & Peace” in Landing Projects’ windows and playing on the transparency between inside and out or what is “mine” vs. “ours,” it is a super direct reminder of what we need both domestically as well as communally.

By CGN Staff via PR

The past several weeks have made many artists and art world players think very differently about how to make and share art with a public that is largely unable to gather in one place. The organizers of a new initiative, based out of Chicago but with a global reach, were inspired by the generosity of artists and the power of art to transform and connect us.

ART-IN-PLACE (AIP) is an initiative of CNL Projects (founded in 2016 by Cortney Lederer) and Terrain Exhibitions (a nonprofit founded in Oak Park Illinois by the late artist Sabina Ott and author John Paulett.) At the onset of the pandemic, these art connectors noticed so many artists began to create and offer to send small artworks in the mail to anyone that asked. Artists were using Instagram as a platform to share this generous offering. They shared collaged postcards (Kelly Kristen Jones and Melissa Oresky), "corona rings” (Laura Davis), seeds to grow (Anna Brown), plant clippings, and other creative works. CNL says they received about five different artworks in the mail within a couple weeks. Art became a way to connect, inspire and bring hope during a moment when we were all so suddenly disconnected from one another. We felt moved and inspired. We wanted to create a platform to share this generosity and consider what we all need right now—connection to others outside the virtual. There is no better tool for this than art.

Visit https://www.cnlprojects.org/artinplace to view participating artists.

The organizers note that due to the fact that over 275 artists are participating (including artist living in Berlin, Canada, Japan, India, Israel and Peru) they are still in process of uploading artists' image details and websites. Click on each artist's image to learn more about each artist and locate an address of where to tour art in your community. A live map is being developed for release next week.

Collectors have the option to purchase a beautiful set of curated postcards showcasing a collection of every ART-IN-PLACE participating artist (forthcoming). Artists collectables, editions and original works of art are available for purchase. Please contact cortney@cortneylederer.com if you are interested in a work of art. From each artwork sale, artists receive 80% and donate 20% to the Arts for Illinois Relief Fund, which provides financial relief to workers and organizations in the creative industries impacted by COVID-19. All proceeds from postcards sales will also support this fund.

ART-IN-PLACE will be on view from May 20–June 20, 2020

AIMÉE BEAUBIEN 2443 N. Francisco Ave. Chicago, IL 60647 Size variable, printed banner material, paracord $3,500 Artist’s Note: What happens when a plant closes its eyes, when it loses its leaves? What will the last leaf look like?For After the Last Leaf, I took stock of my immediate landscape and photographed specific leaves plucked from plants growing inside of my home and in the garden that surrounds. Qualities of the garden run parallel to the nature of photography: they are spaces defined by interactions of the scientific, the accidental and the temporal. Wild, fast growing vines slink through the yard and climb around our house. In my home studio, plants mingle with huge tangles of cut and woven photographs that dangle down from the ceiling in various states of progress and decay. I photograph the ever-changing conditions as plants dry and projects grow.Vines trail, ramble, lean, flop, twine, weave, root, grasp, cling and climb. I translate my responses to the vitality of vines by pushing color while imagining how energy is harnessed from the sun in photosynthesis. I reorganize the scale of my photographs to amplify the ambition of vine movements while translating their enviable ability to embrace everything near in acts of remarkable adaptability. Vines are tenacious. Vines will win.

CECIL MCDONALD, JR. 10026 S. Wood Chicago, IL 60643 40” x 30”Mylar and pigment ink$3,000 Artist’s Note: Car garage wrapped in Mylar, waited for the colors of night, street lamps, car headlights, brake lights and the green of the surrounding nature to reflect in a spectacular fashion for the photograph. The goal was to explore the transformative power of photography.

It is our great pleasure to present the inaugural SF Camerawork Exhibition Award to artist Aimée Beaubien for her proposal Matter in the Hothouse.

It is our great pleasure to present the inaugural SF Camerawork Exhibition Award to artist Aimée Beaubien for her proposal Matter in the Hothouse. This award recognizes a project proposal featuring exceptional creative photographic work, and will support those efforts with an exhibition grant in the amount of $5,000.

Beaubien's proposal was selected to receive the grant from a pool of over 200 applicants. Erika Gentry, Programming Committee Chair, wrote of the proposal, "Beaubien's work stood out for its conceptual strength and innovative presentation, which animates photographs to become a series of moving parts, pushing their capacity to change and to transform. New work funded by this grant will be used to build a photo-based installation utilizing the unique characteristics of the exhibition space at SF Camerawork to map networks of meaning and association between the real and the ideal, memory and the photographic. For Matter in the Hothouse, cut-up photographic forms will interweave, encircle, and hang.”

Qualities of the garden run parallel to the nature of photography: both are defined by interactions of the scientific, the accidental and the temporal. Attentive to perceptual shifts between the depicted and touchable, Beaubien manipulates her photographs into becoming a series of moving parts, pushing their capacity to change and to transform. While walking through one of her installations photographic elements slip between recognition and abstraction. Bold leaf shapes and twisting ribbons of photos entwine, cluster and creep. A photographed plant, interlaced vine, woven topography merge into fields of color and pattern and back again expanding the ever more complicated sensations of reading a photograph and experiencing nature.

The SF Camerawork Exhibition Award will be a part of SF Camerawork's 2021 programming schedule, and we look forward to hosting you all next year for this exhibition.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Aimée Beaubien is an artist living and working in Chicago. Her cut-up photographic collages, photo-based sculptures and installations explore collapses in time, space and place, while engaging the complexities of visual perception. Solo exhibitions include Gallery UNO Projektraum, Berlin, Germany; Virus Art Gallery, Rome, Italy; Johalla Projects, Chicago, IL; Marvelli Gallery, New York, NY; TWIN KITTENS, Atlanta, GA; and Demo Projects, Springfield, IL. Beaubien is an Assistant Professor of Photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL.

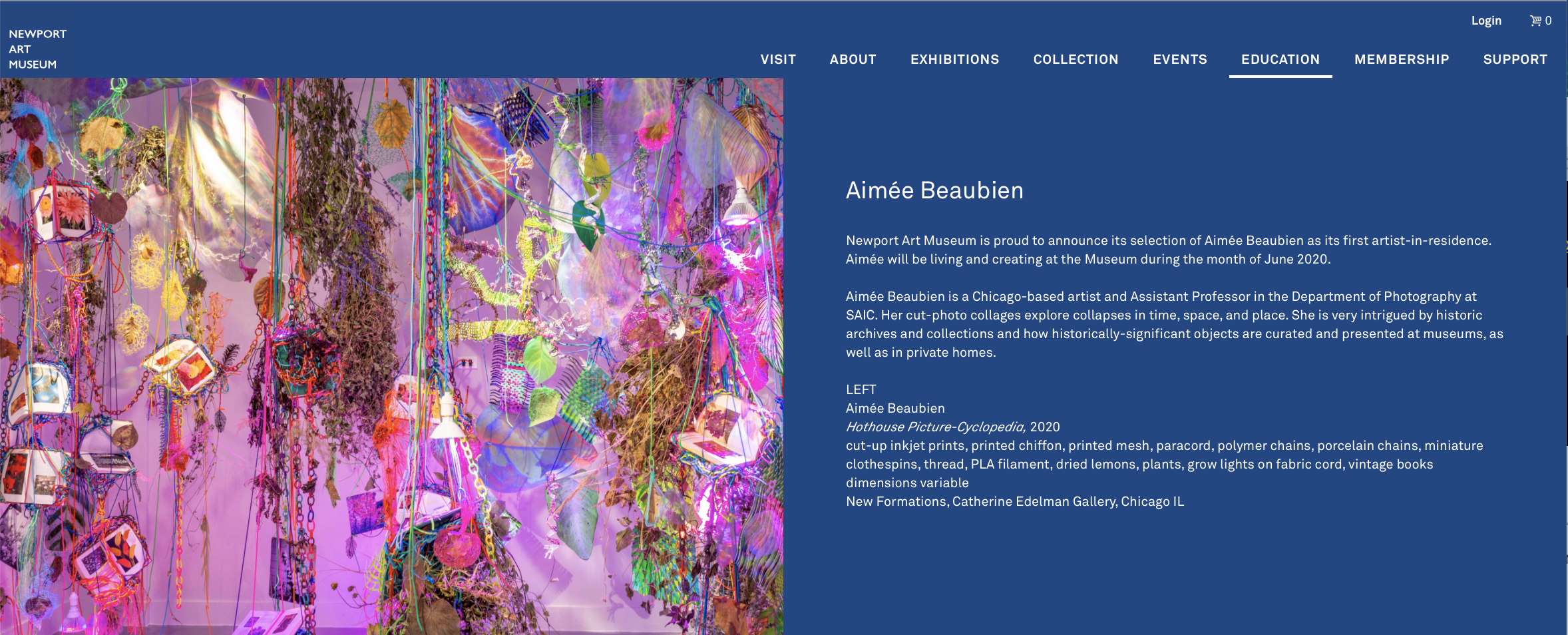

Newport Art Museum is proud to announce its selection of Aimée Beaubien as its first artist-in-residence.

PDN PHOTO OF THE DAY

Between Photography and Sculpture

On January 17, Catherine Edelman Gallery will debut the work of international photographers Nicolás Combarro, Hannah Hughes and Lilly Lulay, alongside well-known Chicagoan, Aimée Beaubien, in “New Formations.”

In a culture where digital photographs are ubiquitous and routine, artists are challenging themselves to find new ways of working with photographic images. The four artists featured in “New Formations” are “reinventing how photography is used to represent a place, object or memory,” writes Catherine Edelman Gallery in the press release. “As the works become more complex, memories are fragmented, places are deconstructed, and objects are recontextualized.”

Procuring images from diverse sources, Combarro, Hughes, Lulay and Beaubien cut, collage, weave and paint to reconstruct photographic prints. “Situated between photography and sculpture,” writes the gallery, “the works in the exhibition go beyond the content of a singular image, introducing a new visual language.”

Beaubien’s colorful work is heavily influenced by her great grandmother, art history and gardens. To bring these elements together, she weaves photographs, drapes rope and suspends old photography books in large site-specific installations that aim to imitate plant growth.

In his series “Spontaneous Architecture,” Cambarro, who lives and works in Spain, paints, collages and draws on architectural photographs. “By focusing on these shapes, he bridges the gap between architecture and fundamental forms found in art,” explains Catherine Edelman Gallery.

After cutting repetitive shapes from glossy magazines, Hughes layers them to create photographic sculptures. The work in her series, “Mirror Image,” alters the significance of the original page while “magnifying the beauty of color and form.” Hughes is based in the United Kingdom.

In response to the sheer number of photographs made in cities and public spaces and the collective memory they create, Lulay, born in Germany, shatters this perspective by cutting and collaging found images into new landscapes.

There will be an opening reception at the gallery on Friday, January 17 from 5 – 8 p.m.

“New Formations”

Nicolás Combarro, Hannah Hughes, Lilly Lulay, Aimée Beaubien

Catherine Edelman Gallery

January 17 – March 7, 2020

Terrain Biennial in ARTnews

A Chicago Biennial Is Taking Art Beyond Museum Walls and Into People’s Yards

BY CLAIRE VOON

October 18, 2019 1:07pm

The Chicago suburb of Oak Park is lined with verdant lawns, many of them dotted with ornaments or “Black Lives Matter” signs. For the next six weeks, however, more unusual decor can be spotted outside several homes: a geodesic dome here, an abstract assemblage there, a bulbous inflatable lodged in an alley. These weatherproof objects are part of the fourth Terrain Biennial, which opened earlier this month, with installations by more than 250 artists showing exclusively in the public-facing areas of private homes, including front yards, facades, and windows.

Terrain’s founder, the late artist Sabina Ott, developed the biennial in 2011 through a gallery she ran from her porch in Oak Park, which remains the exhibition’s nucleus. This edition, organized by a new board of directors, is more expansive than previous versions, with satellite sites in Chicago proper, Los Angeles, London, Portland, Maine, and even faraway locales like Havana, Cuba, and Dhaka, Bangladesh. To visit, locals just have to show up outside host homes—no ticket or appointment is required. (While the diffuse nature of the show means that crowds are unlikely, expect to see dads pushing lawnmowers and kids on bikes.)

The premise of the biennial, which largely spotlights local artists, rests on an anti-institutional, community-first ethos that has long driven Chicago’s rich history of artist-run spaces. But it also playfully mines a more universal tendency. “People use their houses as expressions of their identity in a variety of different ways, from political slogans to holiday decorations,” Tom Burtonwood, a biennial board member, said. “Terrain is a continuation of that history and vernacular.”

This year’s participants—which, like their hosts, are selected through an open call process—were asked to reflect on the changing environment. Naturally, foliage was a common motif in projects. In Oak Park, Aimée Beaubien covered the pistachio-colored facade of her host’s house with an iridescent collage of photographs documenting leaves from her own home. Woven together with paracord, they form a radiant vine—a symbol of tenacity amid shifting ecological conditions. “The inkjet prints will continue to curl,” Beaubien said, “much like leaves crumpling up before falling.”

Elsewhere, collaborators Marina Peng and Rachel Youn riff on the American dream of white picket fences with a 12-panel folding screen adorned with imagery of desert plants. The ornamentation, baroque and begging to be Instagrammed, skewers insatiable consumer cravings for trendy non-native flora. Meanwhile, discarded plant blooms are materials for Rebecca Ann Keller, who repurposed them to build a pair of 6-foot-tall wreaths. Draped with banners that read, “There is No Other,” they are melancholic greetings to passersby, standing as cautionary memorials for a dying planet.

Other contributions are harder to spot, as they nearly blend in with their surroundings. (With Halloween fast approaching, one would be forgiven for thinking some works are spooky decorations.) It would be easy to walk right by Paola Cabal’s tribute to Ott, which traces the shadow cast by a sapling planted by Ott’s husband. (The artist died in 2018 at the age of 62.) Painted on Tyvek attached to the dirt, the dark marks are a poetic symbol of the late artist’s spreading influence on Chicago’s art community.

Just five blocks south, Kelly Kristin Jones’s Native Guard is an effective study in the power of camouflage. On a lawn sit three papier-mâché mounds of photographs of foliage. Only when you read an accompanying text (slipped into a brochure holder) does it become clear that each is a mold of a local historical marker. Jones has been making work around monuments that commemorate racist white men for three years, initially focusing on those in the South when she lived in Georgia. Now based in Chicago, she photographs the surroundings of local sites that honor what she describes as “false and/or violent histories,” and uses edited imagery to digitally “erase” or “heal” the landscape. “Whether such monuments are finally taken out of our public spaces or not, they will forever haunt both our narrative and our land,” Jones said. When Terrain ends, on November 17, she intends to sheathe the original monuments with the molds.

In the suburb of Evanston, several more homes become political sites. Unwieldy sculptures that Óscar González-Diaz fashioned out of a concrete material used for refugee shelters slump on a well-manicured lawn like languishing baggage. Sonja Thomsen’s own sanctuary, a plywood dome decorated with enlarged fragments from the U.S. Constitution, serves as a sunny site to contemplate the current state of democracy. And winding along one street corner is a neon banner by the collective Pixelface, inscribed with messages of solidarity for marginalized groups, such as immigrants, the LGBTQ community, and incarcerated individuals.

The scope of Terrain may overwhelm visitors—especially those who don’t have cars. Relying on public transportation and two feet, I could explore only the Oak Park and Evanston sites over a single weekend. Could all this travel deter art lovers in the Chicago area from seeing every work in this vicinity? Burtonwood said, “Something we’ve been wondering is: Are we a middle-class art project? Is there a barrier to see the work if you don’t have a car? Or is there a barrier to participation? Do you have to have a house or nice landlord? I’m not sure what the answer is.”

A car or bicycle may be helpful when navigating this year’s biennial; a map could probably come in handy too. But Terrain’s charm lies in the delight of happening upon art in the wild, be it sculptures hidden away in shrubbery or cyanotypes waving from a brick wall. Ott was “super focused on the idea of the accidental viewer—the passerby going to school or the store who would happen upon art,” Burtonwood said, adding that the biennial doesn’t ask much of the public. In other words, people simply have to leave their homes and keep their eyes open.

CLAIRE VOON/ARTNEWS

ARTIST TALK: AIMÉE BEAUBIEN HOTHOUSE PICTURE-CYCLOPEDIA

Pushing the Boundaries of Photography in the Third-Dimension by Christina Nazfiger

Eight years ain't bad ‘Collaborations’ is a joint effort between Laney Contemporary, Aint-Bad Magazine

Eight years ain't bad

‘Collaborations’ is a joint effort between Laney Contemporary, Aint-Bad Magazine

By Rachael Flora

"Collaborations" is on view through Aug. 10 at Laney Contemporary, located at 1810 Mills B. Lane Blvd.

AINT-BAD and Laney Contemporary share a strong working relationship.

Back when Susan Laney was at Oglethorpe Gallery, she hosted some of the publication’s first exhibitions. She’s always been a supporter of photography as a medium, both through her oversight of photographer Jack Leigh’s collection and through her support of local photographers.

“Collaborations,” on view at Laney Contemporary now through Aug. 10, is the result of a years-long partnership and the first exhibition of its kind to be held at the gallery.

The work for “Collaborations” was curated from the submissions for Aint-Bad Issue 13, which came out last fall.

Laney, who curated both the exhibition and the issue, was joined by her Laney Contemporary partner Allison Westerfield and by Aint-Bad’s Taylor Curry, Carson Sanders, and Lisa Jaye Young.

The issue had 14 curators, and they went through submissions by around 900 artists.

“We just worked together,” says Laney. “We picked what we thought would be best for the exhibition, and sometimes the actual work on the wall isn’t in the publication, but the artist’s work is. That was fun because we had more to choose from, and it came together so beautifully.”

In addition to the work for the exhibition, Aimée Beaubein created an installation for Laney’s mirrored room, which has been a point of fascination and experiment for exhibiting artists since Laney’s opening.

“[Aimée] teaches at the Art Institute of Chicago, so she flew in from Chicago, put together the installation in four days, freaked out over this room,” remembers Laney. “It was fun to have her energy and her excitement in here. She’s fairly new to installation work—she’s been doing it for two or three years and it’s interesting to see the different kinds of installations she’s done. This one is very different, just because he space is, but also her weaving the photographs and her presentation is different for this.”

While the curators initially intended to keep the submissions within the country, they were able to include some work by a Japanese and a South Korean photographer, which is a great opportunity for Savannah’s viewers.

“We’re presenting work that really has not been seen in this region and is something very different, something we haven’t come close to doing before,” says Laney. “This exhibition is very different from everything else, mainly because of the breadth of work. It’s not just one piece from one photographer. We really zeroed in on Aint-Bad as a publication, the reason for Aint-Bad, the vision of these photographers and the vision of Aint-Bad looking out into what’s going on in photography today.”

“We’ve always, from the beginning, wanted to simply promote the collection and appreciation of contemporary photography, and have it be as affordable as possible,” says Sanders. “Selling a less expensive book or magazine allows more people to collect work from an artist, and having the opportunity to do exhibitions like this really brings home that fine-art aspect of Aint-Bad. To see these beautiful framed works on the wall give the ability for our serious collectors to pick up some works from photographers that may not have been shown in this region before.”

Since its inception in 2011, Aint-Bad’s vision has remained the same, even as staff has come and gone.

“From the very beginning, I’ve been interested in how this group of people, very talented photographers with different talents and skill sets [came together],” says Laney. “They have so many people working with Aint-Bad that are working remotely, which has really been interesting because at first, it was all based here, and as people moved away and took jobs in different places, they stayed connected and it created this incredible community. It’s just been interesting to see how it grew over the years.”

“It’s evolved a lot,” joins Sanders. “We’ve always walked this line between, ‘Is it a book or a magazine?’ It certainly feels more like a book now, but it still is treated like a magazine with a fairly affordable cover price. If you find it in a bookstore, it’s going to be in the magazine section, not on the shelves next to hardcover photography books.”

As Aint-Bad marks eight years, Sanders thinks about its future.

“The vision has been the same, and it’s expanded,” says Sanders. “We’re trying to grow our business, we’re trying to grow ourselves as artists, as creatives, pushing. Taylor [Curry] does all our graphic design, so he’s pushing his creativity to keep up with the trends of various other publications as well as books. The work we’re showing has to be desirable to a large audience or people are going to go to another website or publication to look at work. We’re always trying to push the boundaries and expand ourselves.”

CS

Tags: Art Beat of Savannah, Collaborations, Aint-Bad Magazine, Laney Contemporary, Photography

Hold Sway: Ellen Hanson + Aimée Beaubien

detail: Contact, 2019, cut-up inkjet prints, paracord, carabiners, blue lights on fabric cord, three-ring binder

Hold Sway: Ellen Hanson + Aimée Beaubien

Friday March 15th to April 28th, 2019

Heaven Gallery, Chicago, IL

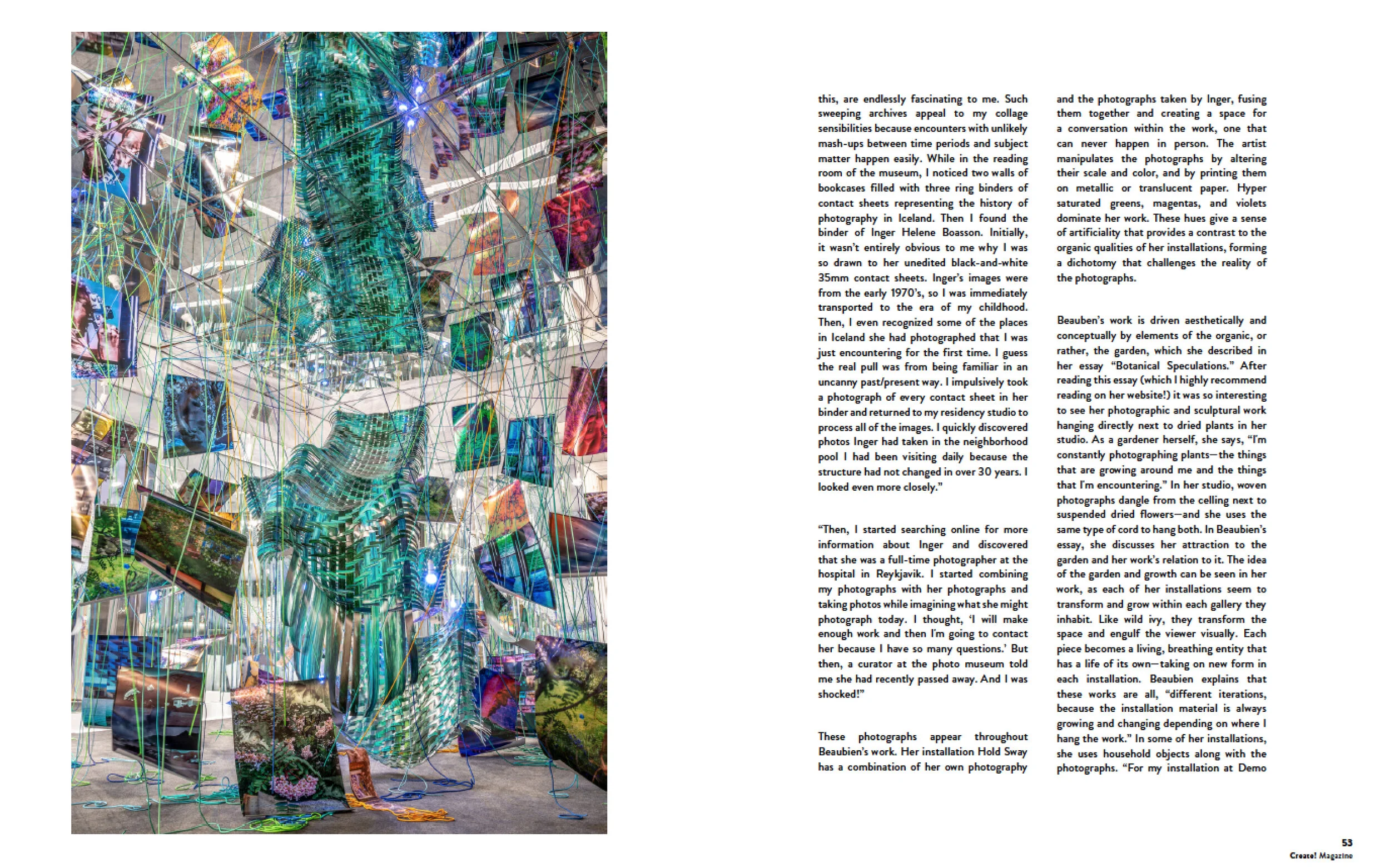

Hold Sway brings together two artists working with overlapping perspectives in paint and photography. Ellen Hanson’s paintings reveal partial views on free-standing intersecting canvases. Inspired by paintings on folding screens, these works emphasize the illusion of the image. Hanson's multi-paneled paintings reveal intimate moments while at other angles their built-in barriers conceal, underscoring the nature of privacy. Aimée Beaubien draws parallels between photographs and landmasses in states of flux. Photos cascade and plates shift in a fractured landscape shaped by subterranean forces. At the core of this photo-based installation is a chance encounter with a three-ring binder of 35mm black and white contact sheets dating from the early 1970’s. Guided by the photographs of Inger Helene Boasson, Beaubien builds bridges between past and future via the visual records of two women, unknown to one another.

-----

Aimée Beaubien is an artist living and working in Chicago. Her cut-up photographic collages, photo-based sculptures and installations explore collapses in time, space and place, while engaging the complexities of visual perception. Solo and two-person exhibitions include oqbo galerie, Berlin, Germany; Gallery UNO Projektraum, Berlin, Germany; Virus Art Gallery, Rome, Italy; SIM, Reykjavik, Iceland; The Pitch Project, Milwaukee, WI; BOX 13 Artspace, Houston, TX; Johalla Projects, Chicago, IL; TWIN KITTENS, Atlanta, GA; and Demo Projects, Springfield, IL. Group exhibitions include Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; Bikini Berlin, Berlin, Germany; Antenna Gallery, New Orleans, LA; Lubeznik Center for the Arts, Michigan City, IN; and UCRC Museum of Photography, Riverside, CA. Her work has been reviewed in publications such as Art in America, Art on Paper, and Art Papers. Beaubien is an Assistant Professor of Photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL where she received her MFA in 1993.

-----

Ellen R Hanson is a midwest based painter traveling between Chicago, IL and Gresham, WI. Her works are about feeling exposed, vulnerable. About watching and being watched. She received her BA from Bennington College in 2014. Her two person exhibitions include Miishkooki (Skokie) and Friendzone (Chicago). She has most recently participated in group shows at Happy Gallery (Chicago), Elephant Room Gallery (Chicago), Heaven Gallery (Chicago) and Produce Model Gallery (Chicago).

With Inger, artists' book made in collaboration with The Donut Shop

At the core of ‘With Inger’ is a chance encounter with a three-ring binder of 35mm black and white contact sheets dating from the early 1970’s. Aimée Beaubien combines her own photographs with those of a stranger. Guided by the photographs of Inger Helene Boasson, Beaubien builds bridges between past and future via the visual records of two women, unknown to one another. Through an unfolding visual expedition of the geographic, architectural, and social landscape of Iceland, Beaubien’s artists’ book embodies an incomplete archive while conjuring a woman whose works were left to the historical periphery.

‘I really didn’t know what to look for when I landed in Iceland for the month of June. Inside the reading room of a museum I systematically surveyed the names written along the spines of three-ring binders. Working my way through an army of men lined up for days and years - really wanting to find a woman represented on the shelves of contact sheets - I randomly pulled binders out to study the range of work. More than two-thirds of the way through, I almost started over, almost gave up. And then I found you.’

In an edition of 25 copies, this is the second limited edition artist book made in collaboration with The Donut Shop.

BOOK DETAILS

41 pages / 91 folds

1 unique dye sublimation print

Edition of 25

Printed on Neenah Classic Crest - Solar White + Neenah UV/Ultra II

3-Ring Bound

Printed with Canon imagePress C800 Color Digital Press

Botanical Speculations

Botanical Speculations

Chapter Four

Gusts in the Hothouse: Aimée Beaubien

Wild,fast-growing vines creep about the garage,slink through the yard, climb upand aroundthe side of our Chicago home.I track their invasive movements.My studio is on the first floor of our house and steps away from the garden.On occasion, I yank out a stranglehold of thickly entwining morning glories, pluck their heart-shaped leaves off and roll rambling trails to dry into large tumbleweeds before they choke too many other plants in our tiny backyard.

I take photographs.I make prints.From my prints, I continue to reconfigure subject matter while reworking images. While examining hand-woven structures, I photograph grass baskets and continue returning to a growing collection of images with the impulse to cut my grass basket photographs apart in order to weave them back together.

When I first started pushing my cut-up photographs into sculptural forms, I grabbed what was within reach to prop material up during construction. In the process of making, I reached for things in my home like cups, colanders, mixing bowls and vases. Very quickly things from my domestic space travelled with my work and into exhibitions; including a growing collection of lemons that had dried before their sourness could be squeezed.

[Fig.4.1] Aimée Beaubien, Chitter-burst-tangle-swell(detail), cut-up pigment prints, wooden dowels, ceramic bowl, glass bottles, ceramic jugs, needle point foot stool, wooden table, and miniature clothespins, 2015, courtesy of the artist Aimée Beaubien

Depictions of a multi-dimensional world rendered flat in prints reach new expressions as I weave visual impressions together. Drooping, pitched and placed.Sloping, jutting, braced.Holding, planted and spread.Leaning, shooting, bedded, staked.My pictured plant forms are constructed through processes of translation, revision, cutting and reassembling; reflecting on the complexity of the garden and of the photographic encounter.

Some qualities of the garden run parallel to the nature of photography: both can be defined by interactions of the scientific, the accidental and the temporal. My approach to building installations feels similar to how I treat my tiny backyard garden. My garden in life, and in the life of exhibitions, is much like a large-scale canvas to explore the potentials of wild compositional experiments.

[Fig.4.2] Aimée Beaubien, Hothouse Cuttings(installation view), cut-up pigment prints, color laser prints, paracord, miniature clothespins, hammock swings, grow lights on fabric cord, dried lemons and limes, 2018, courtesy of the artist Aimée Beaubien

Gardens portray time.Interdependent systems grow, bloom, intertwine and die. With live plants coexisting in my studio with photographs of plant matter, I began to incorporate dried botanical elements into my installations. Death is steeped in photography and dried plants alike.

Photography images the world as beguiling fragments.Our contemporary lives are lived in a series of interrupted fragments. Sampling and re-mixing are interwoven throughout our daily experiences.Cut-up techniques are employed in literature, music, cinema, visual art and popular culture.

Moments drift. I crowd in with my camera to draw connections through different conditions in a manner that I imagine in which information travels through systems and bodies. The act of replacing a complete image in the process of inventing a new one seems analogous to the ways that I process information and reconstruct memories. I think I know something but that thing and my relationship to it continues to transform.

Working in an exploratory manner,I place myself somewhere not entirely familiarand crowded into situations where I learn as I go.During a residency at the Roger Brown home in New Buffalo, Michigan, I learned that, at one point, Roger had a collection of 50 different varieties of roses on his property.I look with photography. While I looked out of Roger’s windowsI re-assembled ribbons of cut photographs into flexible interlocking structures,mimicking the plant movements in front of me.

Many photographic gestures can be traced back to photography pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot. Geoffrey Batchen wrote of Talbot’s photograph of honeysuckle from 1844: “Talbot crowds his camera into the bush of flowering honeysuckle, resulting in a remarkably three-dimensional picture. Looking at this image, we feel as though we too are peering into these branches, our field of vision totally filled by its light-dappled petals and stems. The photograph is at once realist and abstract, and thus points to a paradoxical aspect of photographic vision that many future practitioners would also learn to exploit.”[1]

Throughout the seasons and over her lifetime, my great-grandmother Gertrude photographed the changing conditions in her garden.The many ways that she used her camera to look closely to discover a jack in the pulpitand to hold onto ephemeral matter—like her short-lived blooming peonies—have always loomed large in my imagination. Often my great-grandmother included detailed information about what was not available in her front facing views: “Here’s a picture of my mums.They were 4 inches across.Everyone stopped to look at them!”[2]

I have a timeline of photographic processes over Gertrude’s lifetime and fragmented views into her enduring fascination with the things that grew around my great-grandmother.Her color palates, eccentric compositions, and written observations of what wasn’t picturedwere my first point of photographic contactand remain my most enduring guide.I remember hesitating a long while before declaring the garden as subject,the garden as point of departure.I am an artist with 1970’s toile wallpaper of romantic pastoral scenes still hanging in what is now the entryway to my studio.I am an artist working with family photos.I am an artist photographing flowers. While these categories may only suggest my gender,they do not attest to my dedicated experimentation with the flexibility of photographic imagesand the materiality of photographs for over three decades.My earliest photographic impulses came of a desire to draw attention to how pictures are constructed.

I use photography to record my responses to present conditions in color, pattern, structure, and place. I continue to photograph in my garden, my mother’s garden, as well as public and private gardens while keeping my great-grandmother’s observations in mind.An anthropologist approached me after I presented some of my plant related works at the Botanical Speculations Symposium.[3]She spoke of research about photonic sensation and photonic choreographyas it relates to what she could see demonstrated in the ways that I make my work. 'add period'Charles Darwin was entangled in the daily rhythms of life. His home and garden were experimental spaces where he entered into what has been called a sensory partnership with his subjects.He moved and was moved by subjects in nature.

My work is driven by the transformative potential between image and material, and by the generative and cumulative strategies of making. I use photography to hold onto a short-lived and waning bloom as others have before me. Comprised of partial views, my constructions make physical seams visible where fragments meet and overlap.Collage and sculpture are intertwined in their material making for me.Photography optically frames and records traces of materiality,object becomes image, and then cut-up and woven back into an object again.

I use collage to investigate oscillations between photographic depiction and material form.What may be perceived in my entanglements slips between recognition and abstraction:from a sky, an apple in a tree, into topography.I take whatever I have pointed to with my camera and convert it into tangled inventionsthat overlap and intersect;upending conventions of foreground, middle-ground, background;and flipping expectations of subject, object, and motion. Experience morphs into fields of color and pattern and back again.

My studio is marked by cycles of processes at various stages of development. Hanging dried and drying plants mingle with huge tangles of cut and woven photographic pieces. Matter dangles down from the ceiling in states of progress and decay. Marked by seasonality, by various internal cycles of life moving at different speeds, gardens are conveyors of time from the evolutionary to the ephemeral.I photograph the ever-changing conditions in my studio, as plants dry and projects grow.

Each fall microscopic cells designed like scissors appear where the leaf stem meets the branch to push the leaf away. I excised leaf shapes from my photographs, leaving their rectangular backgrounds intact. The negative spaces within these remnants become an evocative frame suggesting the inevitability of fallen leaves while also resembling dappled light through a canopy of trees. As I stack and bind remainders together, I am reminded of the collection of pages in a book. It is noted that in 1,789 poems, Emily Dickinson refers to plants nearly 600 times. The herbarium collection she created contains more than 400 plant specimens. Archeologists have been uncovering and restoring Emily Dickinson’s garden in an effort to better understand her personal physical world and source of imagination.[4]

[Fig.4.3] Aimée Beaubien, Cuttings (detail), 142 page spiral bound artist book, 2017, courtesy of the artist and the Donut Shop Aimée Beaubien

Gardens are collections.They are nature gathered together in public space or private refuge.Interdependent systems grow, bloom, multiply, intertwine and die. Photography is used for many purposes that extend far and wide.Concentrated material investigation guides new developments in my work.I use photographic paper as sculptural material testing the flexibility of printed images. With photography, I weave visual impressionstogether.

What is building inside my studio is connected to what is happening on the outside and inside of our tiny garden. The excitement of spring’s arrival in my garden inevitably makes its way into my work as moments from my everyday have become integrated into the structures of my sculptures and installations.I interact with familiar photographic observations and push them into something else.Forward or backward, reaching or touching, pulling between inside and out.I think I know somethingbut that thingand my relationship to itcontinues to transform. I put things together with photographs because they are charged with the specificity of a caught momentthat is inherently associated with the medium.

[Fig. 4.4] Aimée Beaubien, Collecting Within(detail). Artist book with a stack of 60 accordions in origami cube, 2017, courtesy of the artist Aimée Beaubien

When vines started growing on one side of our home, I followed their growth patterns. In my garden installations, cut photographic forms interweave, encircleand hang; trail in ribbon-like shredsand become wild ornamental outgrowthsas I move with and am moved by living forms. The vine wrapping around our home finally reached my second-floor bedroom and climbed into my dreams.I could feel the vine pass through the window just one foot from where I sleep and enter into the left side of my body while woven elements from my work travelled in from the right to meet somewhere in the middle for an entwining dance.

As objects from my home have made their way into my work, I have found parallels to respond to in different exhibition environments. Each new version in an ongoing series of Hothouseworks offers a garden space defined by interactions of order and disorder. Bold leaf shapes and twisting ribbons of color entwine, dangle, cluster and creep in makeshift exhibitions. The conditions of different exhibition sites inform a new chain of experiential shifts between visual representation and the physical encounter. Gusts in the Hothouse was a completely enclosed terrarium for my garden photos. I placed grow lights and a household oscillating fan inside the glass box to keep my double-sided photographs gently swaying with movement and suggestive of living things soaking up the magenta glow.

[Fig.4.5] Aimée Beaubien, Gusts in the Hothouse,2016, cut-up pigment prints, paracord, miniature clothespins, grow lights, oscillating fan, 2016, courtesy of the artist Aimée Beaubien

InCamera Lucida,[5]Roland Barthes wrote about his relationship to a photograph of his mother when she was a child and standing in a glassed-in plant conservatory.This winter garden photograph that we never see, is the catalyst for a deeply personal investigation into the nature of photographs that includes meditations on the relationship of images to death, time, memory and desire.I re-photographed a teeny, tiny photo Gertrude took of a woman in a flowing flower print dress,absorbed in a weepingcherry tree. Then I cut and wove it together with photographs that I had taken over 20 years ago in the Palm House Conservatory at the Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna.

[Fig.4.6] Aimée Beaubien, Taken, cut-up pigment prints, 2017, courtesy of the artist Aimée Beaubien

Gardens are solace: of leisure, labor, and our attention.They are displays for botanical taxonomies, for our fascination with nature and our desire to order it. In 1989, I walked with my mother through Claude Monet’s spectacular garden where he lived and worked from 1883 until 1926. I look closely into an amazing garden my mother continues to create and think that I see glimpses of the interior life of someone I find hard to know. I recognize patterns in the things I photograph. A still image is never really as static and frozen as it may appear.

Different seeing areas in the brain map the scene to string together movement, color, depth, and shapein order to organize an impression informed by the many observed parts. I reorganize available visual information, modifying the experience and speed of recognition.How much can I cut away?What will agitate associations? I put things together and tear them apart in performances of revision.I vacillate between producing connective momentsand making active gestures extending marks across the field of view,often creating turbulent conditions.

Directed by experience, feeling, thought and uncertainty;between the focus on the line and the focus on the edge and the field of focus presented in the photograph.I construct collisions between what appears on the surface of imagesand what is made absent through acts of incising and extracting.

One image becomes the starting point and then I build picture-relationshipswhile drawing connections between different pictured conditions.Often there are pictures inside of pictures and shapes that I have reshaped.I travel through illusionistic planes to create these tangles, knots, and webs,as I weave an emotive fabric together.Through it all, I continue to manipulate my photographs into becoming a series of moving parts,pushing their capacity to change and to transform experimenting with the many ways that I can alter the sensation of reading a photo.

Where does meaning appear on the surface of things captured?Propelled by the provocative nature of the push and pull between recognition and abstraction,I fill openings, re-write moments and rework experiences, as is often the case in the act of recollecting.While the individual photographic components may be easily reproduced it is my hand that makes each of these thousands of cuts.I never bring all of these elements together in precisely the same manner more than once.

Subjects are veiled, environments turned upside down, cut open and apart. Before cutting up any photographs from Gertrude’s archive, I transcribe all of her captions.On the back of her fading, partial view of Hawaii from October 1965, she wrote: “Put these rainbow pictures together and you see whole rainbow.”[6]I keep looking for all of the others. While photography offers a realistic window onto the world I continue changing the shapes of my windows.

Q&A

Giovanni Aloi:How are your intricate installations stored after they come down, and of course you can reverse that question, how are they set up? They look extremely laborious and delicate. So, that's my question ‘A’. My question B which is “what's the role of beauty, in a classical sense, in your work?”

Aimée Beaubien: I've lots of different storing methods. A lot of things are affixed to my ceiling. Oh, I will say that I was the first artist to ever deliver artwork in giant garbage bags to the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and the curators thought it was hilarious. So, yes, there's artwork all over the place in bags, underneath, and on top of things, everywhere. I do reuse all materials, and so I am always trying to take things apart and put things back together and find new ways to push the material around.

Our relationship to beauty isn’t purely subjective when external influences shape beauty standards. While my work possesses characteristicsof beauty I haven’t felt compelled to isolate a flower to proclaim its supreme beauty. Rather, I build lush, layered environments and create a complex of interconnectedness that embraces the complicated nature of beauty.

Audience:Plants have been objectified in the history of representation — this applies to painting as well as it does to photography. Does your work comply or challenge past notions of objectification?

Beaubien: I use my camera to look closely at plants. Through this open-ended close-looking approach I create collections of printed records to look at again and again. Often, I distort scale relationships, push color around and cut my notations up to completely reorganize the material and experience. I weave together prints on paper to build a series of interdependent components used to construct immersive environments. These paper-objects are not fixed in order to explore alternative configurations for each exhibition. I pay attention to plant movements and explore potential sensations through the many ways that I weave my impressions together. While observing plants and following vines, I think about ways to translate their gestures and patterns of growth through the conditions that I create.

Aloi:What are the specific technical challenges that working with collaged three-dimensional pieces entail? I am thinking more specifically about the materiality of the photographic medium, its durability, and fragility.

Beaubien:At first, I built terrible fragile sculptures of woven photographs that teetered and wobbled on precarious stacks of furniture. Only the tension in the weave of the prints held my photo sculptures together making everything ridiculously difficult to transport. Now I make components that are much easier to move around and manipulate in direct response to each specific exhibition space. I play with weight and balance while constructing makeshift networked systems. Everything I make is laborious. The processes I naturally gravitate towards require time, energy, patience, and skill. I have tested many different inkjet paper types to determine what materials hold up to a certain degree of handling required in the making of my layered installations. Some physical stresses can be too much for the paper to bear. Through experimentation, I continue to discover crucial make-or-break thresholds in my studio to be better prepared for what may occur when on location installing new works.

Audience:What plants do you grow in your garden and what framework of ideas justifies the inclusion of some plants and the exclusion of others? Do you have favourite plants?

Beaubien:A scraggly rose, hens-and-chicks, bee balm, daylilies, mint, wild strawberry, Queen Anne’s lace and moss were in the yard before we arrived and have a strong will to survive. We transplanted much from the first garden I worked on with my husband when we moved about a decade ago. Spring flowers may be my favorite after extra-long cold seasons in Chicago. During the waning days of winter excitement builds with the first emerging crocus followed by patches of daffodils, hyacinth, tulips, allium, bleeding hearts and every year I regret having not planted more bulbs. We introduce a little something here and there to see what might happen in relationship to already established Solomon’s seal, lungwort, brown-eyed Susan, clematis, peonies, purple coneflower, lupine and varieties of hostas, columbine, sedum, lilies, ferns, and hydrangea. Pots are placed on shelves running along the length of the garage and are filled with herbs and some annuals. A wild grape vine from three houses over began wrapping itself around our garage a few years ago and now climbs one side of our home. I fight with morning glories throughout the growing season but let some grow along our shared fences. I track their growth patterns and yank them out in bulk whenever their stranglehold on neighboring plants appears to threaten. Some of our oldest plants were gifts from friends splitting specimens in their thriving gardens. We never have a master garden plan but after answering this question I actually have greater appreciation for what is happening in such a tiny city yard!

[1]Batchen, Geoffrey, and Fox Talbot, William Henry (2008) William Henry Fox Talbot.Phaidon Press

[2]Handwritten on verso, c-print, circa 1950’s, from archive: Gertrude Bastien, born 12, Mar. 1985, died Sept. 1982.

[3]“Botanical Speculations Symposium.” School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 29 Sept. 2017,

www.saic.edu/academics/areasofstudy/artandscience/conversationsonartandscienceseries/events/botanical-speculations-symposium.

[4]Farr, Judith (2016) The Lost Gardens of Emily Dickinson, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press)

[5]Barthes, Roland, and Howard, Richard. (1981)Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. (New York City: Hill and Wang)

[6]Handwritten on verso, c-print, Oct. 1965, from archive: Gertrude Bastien.

30 second documentation of some of my installations from 2015 to 2018

Curator's Choice, Issue No.13 Top 100

AINT—BAD

AIMÉE BEAUBIEN

Published on December 5, 2018

by Kayla Story

Aimée Beaubien lives and works in Chicago, IL. Her photo-based collages, sculptures and installations explore collapses in time, space, and place, while engaging the complexities of visual perception. Beaubien experiments with perceptual shifts between the depicted and the touchable. Solo and two-person exhibitions include oqbo galerie, Berlin Germany; Gallery UNO Projektraum, Berlin, Germany; The Pitch Project, Milwaukee, WI; BOX 13 Artspace, Houston, TX; Johalla Projects, Chicago, IL; and Demo Projects, Springfield, IL. Group exhibitions include Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; UCRC Museum of Photography, Riverside, CA; Art Exhibition Link Castello di S. Severa, Italy; Bikini Berlin, Berlin, Germany; and Antenna Gallery, New Orleans, LA. Her work has been reviewed in publications such as Art in America, Art on Paper, and Art Papers. Beaubien is Assistant Professor of Photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

I embrace the documentary capacity of the camera, recording what I encounter. Since its origin, photography has been used to capture, preserve, and accumulate information: arresting fleeting phenomena as visual records. My approach to photography is iterative, recombinant, and gestural. I ask questions that re-imagine photography. I explore generative and cumulative strategies of making, fascinated by the alterations of format, context, scale, experience and site.

Photographic paper is my sculptural material. Through it, I experiment with perceptual shifts between the depicted and the touchable. My images become printed photographs, then sculptural forms. Cutting, weaving and reassembling, I transform my photographs into complex sculptural interventions that disrupt the rectilinear format and traditional conventions of photographic display. These collage-based sculptures and installations are interative, growing and altering within new architectural contexts.

My recent work reflects on the garden and the photograph as parallels: aesthetic spaces where the impulse to collect confronts ephemerality, and taxonomic order meets unpredictable elements. In my garden installations, cut forms interweave, encircle, and hang; trail in ribbon-like shreds; and become wild ornamental outgrowths mapping associations between the garden, the ephemeral, and the photographic.

I am captivated by many different types of collections, from the significant objects curated and presented by museums to idiosyncratic displays in homes. My photographs are often made in institutional exhibits of art and artifacts, in quirky home museums, in urban plant conservatories, and in my domestic space. I often allow everyday objects from my domestic space to become integrated into the structure of my sculptures and installations. I am fascinated by the translational spaces between image and material. Surrounded by suspended, propped, and perched objects, I reflect on our entanglements with the objects and images we collect.

To view more of Aimée Beaubien’s work please visit their website.

Curator's Choice, Issue No.13 Top 100

Details :

8.25″x10.75″, 256 pages,

Perfect Bound

Edition Size 1500

ISBN : 978-1-944005-18-4

Printed in the Netherlands

Introduction by : The Editors

Guest Curators and Interviews by :

Alan Rothschild

Amy Elkins

Anna Skillman

Heavy Collective

Jennifer Murray

Kris Graves

Michael Itkoff

Paloma Shutes

Paul Kopeikin

Rachel Reese

Robert Lyons

Small Talk Collective

Susan Laney

Zemie Barr

PICKUP YOUR COPY TODAY!

Filed under Article, Curator's Choice, Issue No.13 Top 100

Tagged aimeebeaubien, chicagoartist, Issue No.13,photoinstallation, photoweaving

With Inger, artists' book made with the Donut Shop

At the core of ‘With Inger’ is a chance encounter with a three-ring binder of 35mm black and white contact sheets dating from the early 1970’s. Aimée Beaubien combines her own photographs with those of a stranger. Guided by the photographs of Inger Helene Boasson, Beaubien builds bridges between past and future via the visual records of two women, unknown to one another. Through an unfolding visual expedition of the geographic, architectural, and social landscape of Iceland, Beaubien’s book embodies an incomplete archive while conjuring a woman whose works were left to the historical periphery.

BOTANICAL SPECULTATIONS

Book Description

Ground-breaking scientific research and new philosophical perspectives currently challenge our anthropocentric cultural assumptions of the vegetal world.

As humanity begins to grapple with the urgency imposed by climate change, reconsidering human/plant relationships becomes essential to grant a sustainable future on this planet. It is in this context that a multifaceted approach to plant-life can reveal the importance of ecological interconnectedness and lead to a more nuanced consideration of the variety of living organisms and ecosystems with which we share the planet.

In Botanical Speculations, researchers, artists, art historians, and activists collaboratively map the uncharted territories of new forms of botanical knowledge. This book emerges from a symposium held at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in September 2017, and capitalizes on contemporary art’s ability to productively unhinge scientific theories and certainties in order to help us reconsider unquestioned beliefs about this living world.

Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 49

Gusts in the Hothouse

Aimée Beaubien

SOME RECENT FINDINGS // Curated by Andrew Kensett

Some Recent Findings

The twenty-four artists represented in this portfolio consider two acquisitive potentials of photography: to collect visual records of experience and to produce objects that may themselves be collected and circulated. Their artworks constitute findings both in the sense that their content is, in one sense or another, found and in the sense that they represent new knowledge generated through experimentation. They stretch the capacity of photographs to take on and lose meaning—to cross-contaminate with new environments, materials, images, and perspectives and to be changed in the process. These artists assert that a photographic object and the image it bears can never exist in isolation. Its meaning is made through memories, memes, histories, and fictions.

Some of the artists represented here assert the presence of photographs by incorporating them into sculptural installations and still life arrangements. Many have used analog, experimental, and hybrid processes to reproduce and transmute their images, encouraging particular readings of their content and calling attention to their corporeal qualities. (If one personified the photographs, these transformations would be harrowing: they have been cut, cloned, spliced, burned, and slopped with chemicals.) Others included in this portfolio use photography to examine various archives, which range from institutional to personal and contain both photographic and non-photographic materials. Still others probe photography’s evidentiary role; photographs are deployed here both to question the historical record and to lend credibility to fabrications. All of these artists understand that a change in a photograph’s context, a transformation of its physical form, and an alteration of its image content may each equally influence its reception.

These twenty-four artworks prompt questions. Why do we consider images ephemeral? Why should we think of ourselves as permanent, and the pictures we create, live with, and leave behind as transient? Isn’t it much more often the case that we make appearances in the lives of photographs? That they, these immotile and more or less durable things, will outlast us, as long as there is somebody new around to look?

—Andrew Kensett

Included artists: Noritaka Minami, Jo Ann Chaus, Yajing Liu, Veronika Pot, Marcus DeSieno, Andy Mattern, Elizabeth Albert, Dominic Lippillo, Jeroen Nelemans, Fatemeh Baigmoradi, Edouard Taufenbach, Paulo Simão, Arden Surdam, Martin Venezky, James Reeder, Nancy Floyd, Aimee Beaubien, Alyssa Minahan, Larson Shindelman, Aline Smithson, Tamara Cedré, Amy Friend, Jessica Buie, Tianqiutao Chen

AINT—BAD ISSUE NO.13

Meet Aimée Beaubien, Artist and Assistant Professor

Today we’d like to introduce you to Aimée Beaubien.

So, before we jump into specific questions about the business, why don’t you give us some details about you and your story.

My great-grandmother cutout her face from a snapshot and attached it to the body of a topless woman advertising control top pantyhose for plus-size women. She placed this provocative collage at eye level on her refrigerator in an effort to manage her desires. I remember making things with my great-grandmother from the many materials that she creatively repurposed. Over one summer break, we constructed an extra special pillow for her cat Ting-a-ling stuffed with cat hair saved from regular brushing sessions. During another visit, we cut apart her wedding dress to make a new wardrobe for the doll from her childhood. As a result of these primary experiences, I have been cutting apart my photographs since the 1980’s to test the flexibility of images in an effort to understand the power of photographic representation.

Overall, has it been relatively smooth? If not, what were some of the struggles along the way?

My family was highly mobile; we never lived anywhere for very long. This lifestyle has always been difficult to explain. So many things were confusing from move-to-move and from state-to-state. Chicago is the longest I have lived anywhere, a place where I continue to learn how to connect with others and maintain meaningful relationships. Over the years, I have met many artists with numerous relocations in their personal histories. The process of acclimating to new environments may have provided some kind of unintentional training to look closely, to discover creative ways to process personal observations and experiences. If it is easy to make things then the struggle can be finding value and an appropriate context for what is produced.

Alright – so let’s talk business. Tell us about Artist and Assistant Professor – what should we know?

I am an artist and a professor. I have always felt compelled to know why people make things. While working in my studio I remind myself of the advice that I share with my students in order to feel more emboldened to keep taking chances. Every day I think about what a photograph is and delight in the surprises and slipperiness of an ever-changing medium. Through many years of experimentation, my collages have grown from flat wall-based works into cutup photos in relief. My images printed on photographic paper are now the primary material I use to build sculptural forms and site-specific installations.

Who else deserves credit – have you had mentors, supporters, cheerleaders, advocates, clients or teammates that have played a big role in your success or the success of the business? If so – who are they and what role did they plan / how did they help.

My parents encouraged me to find a boarding school after I transferred to three different schools for ninth grade. I very happily spent my last two years of high school living at a boarding high school for the arts on a lake in the middle of nowhere. We spent our mornings in academic classes and afternoons until lights-out working in our chosen area of concentration. So many decades later this is still my favorite way to divide the day. I landed in Chicago as a sophomore to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) where I have now been teaching for twenty years. Generations of amazing talent have passed through SAIC. I am grateful to be surrounded by amazing alumni, students, staff, and fellow faculty that contribute to a dynamic and inspiring interdisciplinary environment. Who deserves credit – everyone who has helped along the way – too many to name and no way to have done this alone – thank you!

Contact Info:

- Website: http://www.aimeebeaubien.com/

- Email: aimeebeaubien@gmail.com

- Instagram: @aimeebeaubien

- Facebook: Aimee Beaubien