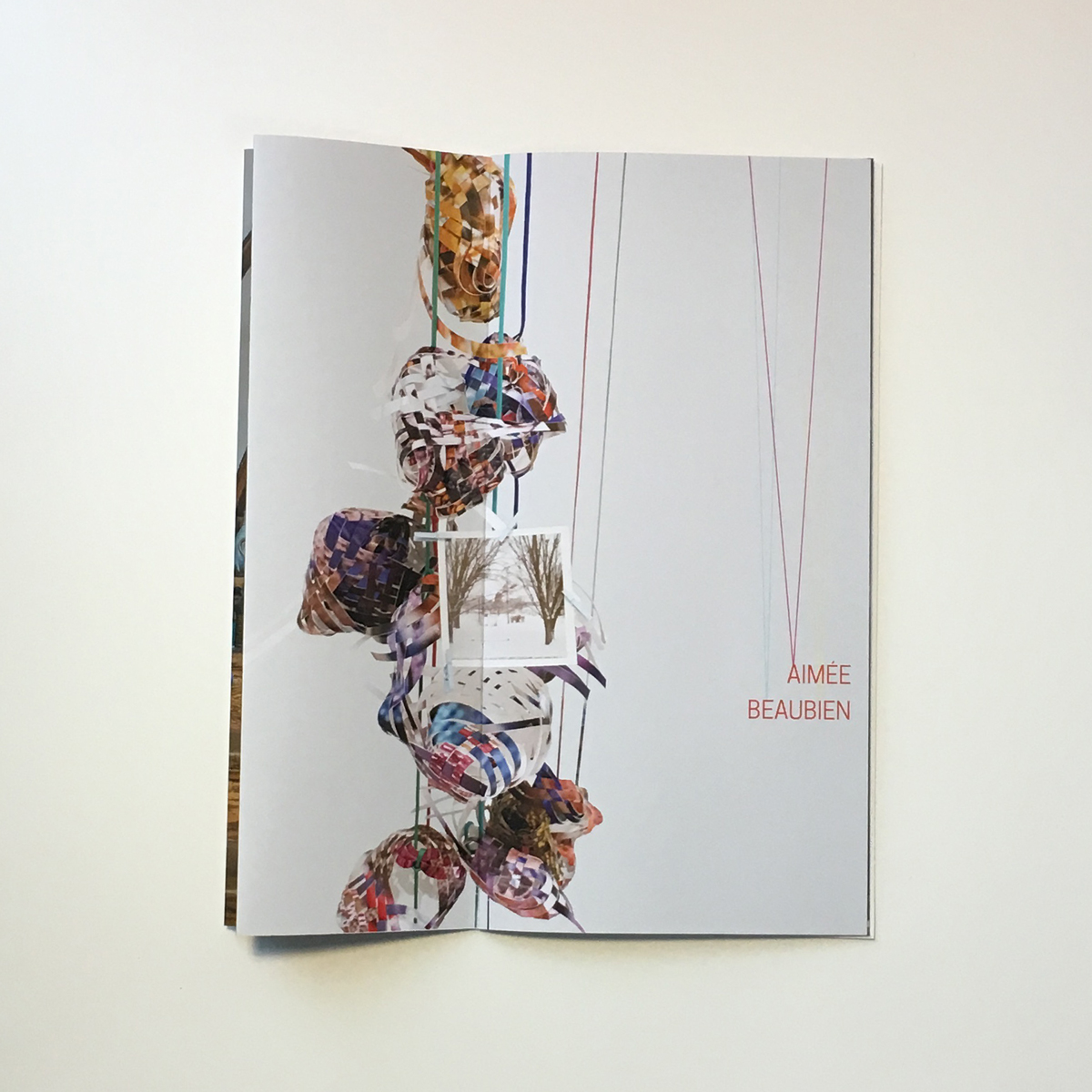

Submissive Exhibitions is pleased to announce the opening for Aimée Beaubien's solo exhibition Hothouse flipside.

In Hothouse flipside, bold leaf shapes and twisting ribbons of color entwine, dangle, cluster and creep in a makeshift basement garden. Botanical life is drawn in the illusory space of photographic representation, or drawn with scissors. My photographs are cut into colorful shapes that interweave, encircle, and hang; trail in ribbon-like shreds; and become wild ornamental outgrowths. Visual oscillations between form and image reflect on the perceptual shifts between photographic depiction and physical encounter.

Gardens are marked by time. Various cycles of life move at different speeds. Interdependent systems multiply, bloom, grow, intertwine, and die. My subterranean garden is constructed through processes of translation, revision, cutting and reassembling, reflecting the temporal complexity of the garden, and of the photographic encounter.

Blog

Gusts in the Hothouse on view until Feb. 15th, 2017

From a visit with INSIDE\WITHIN's Kate Sierzputowski and Ashleigh Dye

Our conversation trailed through the studio and into garden with INSIDE\WITHIN's Kate Sierzputowski and Ashleigh Dye. Thank you both for continuing to provide such great insight into the workspaces and processes of artists connected to Chicago.

Aimée Beaubien’s Woven Imagery

Collecting images like objects, Aimee slices her photographic documentation into pieces that are then woven into large three-dimensional forms. These works, which often hang collectively from the ceiling, are filled with information and bits of data from friends, family, and strangers’ personal collections. By intricately collaging the photographs Aimee allows personal histories to align with those from collected sources, using photographs taken at places such as the Roger Brown Study Collection and Museum of Contemporary Photography.

INSIDE\WITHIN

Aimée Beaubien’s Woven Imagery

Collecting images like objects, Aimee slices her photographic documentation into pieces that are then woven into large three-dimensional forms. These works, which often hang collectively from the ceiling, are filled with information and bits of data from friends, family, and strangers’ personal collections. By intricately collaging the photographs Aimee allows personal histories to align with those from collected sources, using photographs taken at places such as the Roger Brown Study Collection and Museum of Contemporary Photography.

I\W: Could you talk a bit about your source imagery for your collages? Are they typically photographs that you take yourself?

AB: Approximately 99 percent of the images I use in my collages are photographs I take myself. From time to time however I do incorporate some images that my great grandmother made. She made photographs every day of her life, and I inherited her archive, which dates all the way back to 1910. She had this collage on her fridge while I was growing up as a kid that has subconsciously influenced every single artistic move that I have made in my practice. Every once in awhile I will rephotograph her pieces, or just include originals in my installations. She was my primary influence, and was the first to teach me about collage. I keep returning to her work because it was such a potent part of my visual vocabulary as a child.

I\W: How did your residency at the Roger Brown Study Collection influence your practice?

Well, this particular installation that I have in my house was compiled from images I took within the collection. I spent an entire year moving in and out of the collection in both of his homes in Lincoln Park and New Buffalo, Michigan. Brown and his partner were really ambitious collectors, and collected everything from popular culture to really amazing outsider art. He also had all sorts of indigenous crafts from all over the world. His tastes were wild and all over the place. It has been fun for me to consider how his personal collection informed the decisions he made in his own production, how my personal collection informs what I do, and then how most artists implicitly collect, even the ones that consider themselves minimalists.

I\W: Was this the experience that inspired your piece at the Museum of Contemporary Photography for their 40th anniversary exhibition?

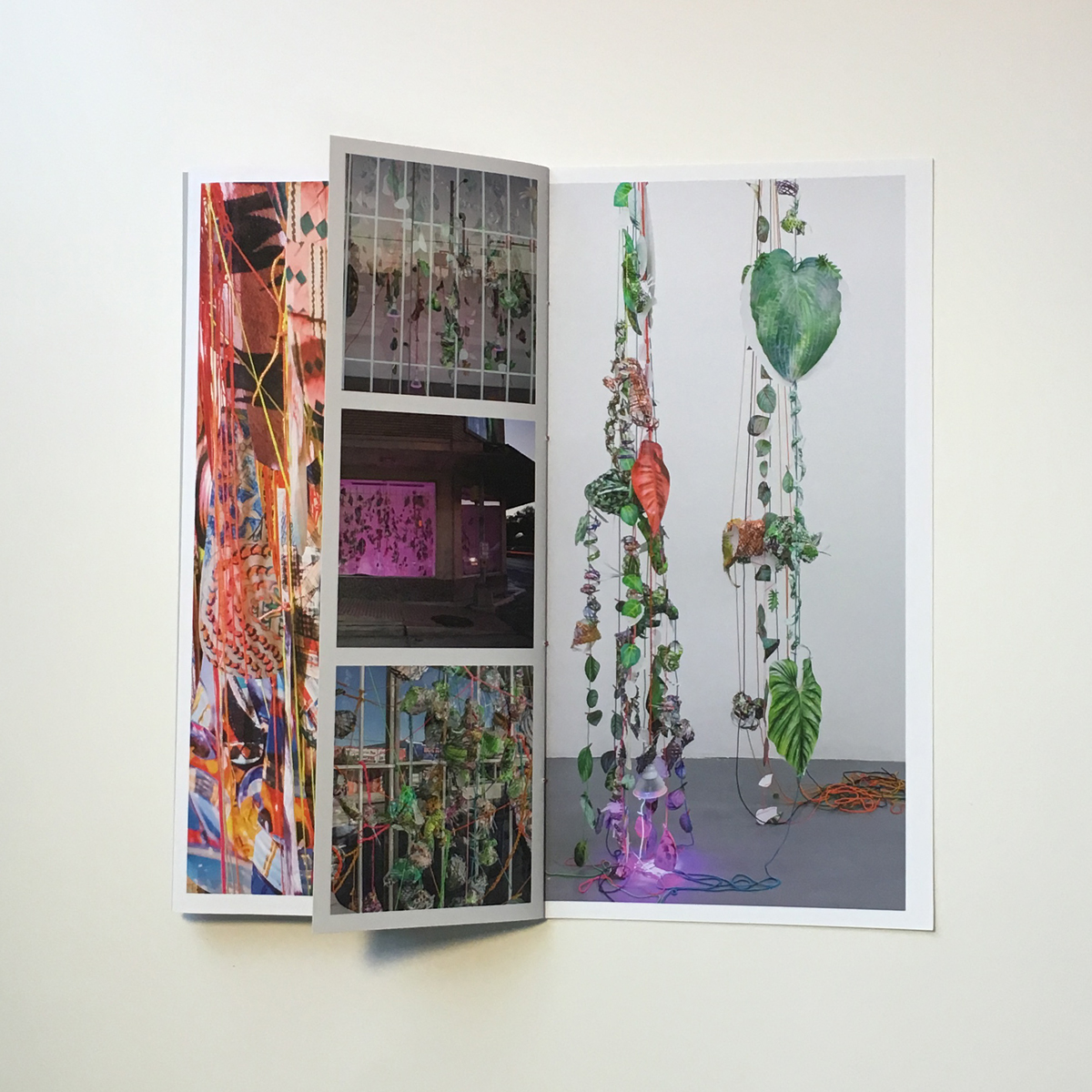

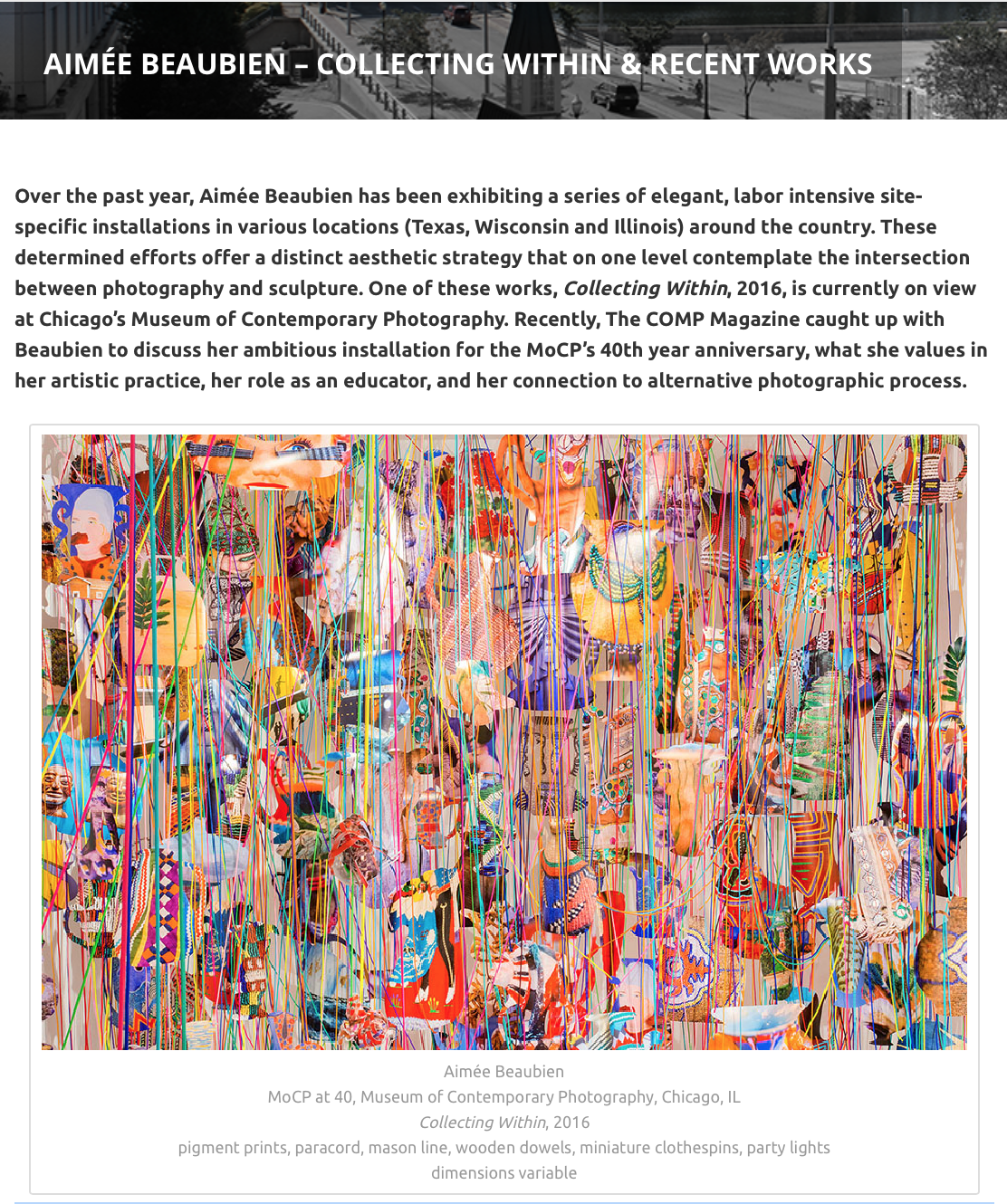

I wanted that installation to look like a cabinet of wonder and to be thick with material. That was my experience being in Roger’s space. There is just work that covers the space from floor to ceiling. It is all so overwhelming and exciting and dense. I really tried to capture that feeling or that intensity. The piece was an iteration of what is currently in my home but much, much larger. The final installed work was 11 feet tall, 9 feet wide, and 3 feet deep. I condensed it for this space when it returned to my studio, but here is where I really worked it out before it was installed in order to get a sense of how much material I needed.

I\W: How did you incorporate your own collection into the installation to mirror Roger Brown’s?

Well, the museum exhibition was specifically about highlighting and celebrating 40 years of their own collection, so when they invited me to do this site-specific piece, I just started thinking about what aspects of the history of photography were most important to me. I always go back to William Henry Fox Talbot and these photographs he took of his personal collection. Also, my work was installed in the museum’s stairwell which was important for me because of the separation my stairwell in my home provides. It is a link and divide between my studio space and my living space with my husband. Our stairwell is covered with my husband’s whiskey jugs, so everything came together when I started to think of these vessel forms I walk past daily on my staircase in relationship to the vessels in Talbot’s still lifes. I then began connecting them to my images of Roger Brown’s collection and started considering my photographs as these vessels of memory. So I began cutting silhouettes of vessels into photographs.

I\W: You are layering diverse histories within your collage, including your own. However each of the works ends up being so bright and joyful. Is that an intention in your installations, or is that just what your eye is drawn to when photographing the world?

I manipulate the color within my photographs. I tend to gravitate towards bright color palettes, but I’m also pushing my works towards them as well through digital manipulation. A lot of that has to do with these colors I am discovering in my great grandmother’s work, especially as the works age. They have a really warm past. When I first worked in photography I was working in the dark room. I was drawn to color and would apply it to the monochromatic work, but I didn’t really know how to incorporate it fully. When I made the transition to digital I went crazy and I remain super interested in experimenting with color.

I\W: Can you talk about your process when creating your 3D collaged forms? How did your work move from 2D to 3D?

Some of the 3D work came out of a project I created at DEMO Project in Springfield, IL, which I consider my very first site-specific installation. While preparing for the exhibition I was noticing how my domestic studio environment was influencing the decisions I was making in my work, and I was excited about having a house as an actual site for the exhibition. For that show I created this huge pile of furniture and then built a giant beanstalk. It looked as if it was growing and overtaking everything, which was based on some things that were happening in my backyard. I had let some vines get out of control because I was interested in watching their woven patterns and observing how they overtook other plant life. I was also reading JG Ballard’s post-apocalyptic novel The Drowned World that he wrote in the 1960’s. I was excited about the chaos of a domestic space being overtaken by this natural form. That prompted this whole weaving of the image thing, which started last summer.

I\W: Why did you decide to weave the images together?

Right before the exhibition at DEMO Project I had visited Santa Fe, NM. I went to a gallery recommended by a friend that had these amazing baskets and I asked if I could photograph them. I spent hours doing this, but couldn’t figure out what to do with these photographs. I decided to just cut them apart and weave them back together into basic basket forms. I am really confused about how to visually understand the way digital information is captured and converted into 1’s and 0’s and then turned back into an image again. For me, my woven images are weird metaphors for these digital processes I don’t seem to fully understand. I am physically pulling the images apart and then putting them back together again.

I\W: Why do you choose to leave untouched photographic moments in your work alongside the more sculptural pieces?

One thing that is interesting to me is how frequently people who are active viewers of collage automatically leap to the conclusion that it is appropriated imagery. I totally get that based on the history of collage and the way that I often photograph other people’s artwork, so there is definitely a nod to appropriation, but they are still my photographs, and they still are radically different from what the original source image may have been. I thought about experimenting with this idea of potentially reintroducing more whole moments from my photographs. I don’t really know what this is yet. It is a newer impulse that I feel is an outgrowth of this satisfaction in making the vessel forms. I think I am trying to figure out if I would be comfortable making a rectilinear photograph which I have not done for a very long time. Or is it more exciting for me to cut forms out of my rectilinear photographs? How much can I cut away? When do you recognize the form as a photograph? When is it just material? For me there is so much meaning in the making of these things. I think that it is a really charged visual experience to make them, but to also view them and experience them.

I\W: Now that you have been making the sculptural forms with your photographs, does this influence how you capture the original image?

Totally. I think that is why I play so much with shallow depth of field. I think about an out of focus area more as fabric. I think everything really shifted for me when I did a residency in Austria and it happened to coincide with the Venice Biennale. I decided to spend a week there photographing. I thought I would just make photographs as documentation of exhibitions to share with my students, and then I noticed I was taking photographs in really weird ways. I wasn’t documenting the shows. I was really interested in the intersections between the contemporary art and then this really robust decorative palace. It was such an incongruous and exciting meet-up for me. I decided that this could be material to make work from. I started photographing things differently because I was already anticipating cutting them up.

Studio Visit Takeaway

Arndis Ortharsson's beautiful printed piece for twist-flip-tremble-trace, 2015

Gusts in the Hothouse

Gusts in the Hothouse, 2016

THE COLLECTION | Where Art Meets Fashion | Fashion Outlets of Chicago | Rosemont, IL

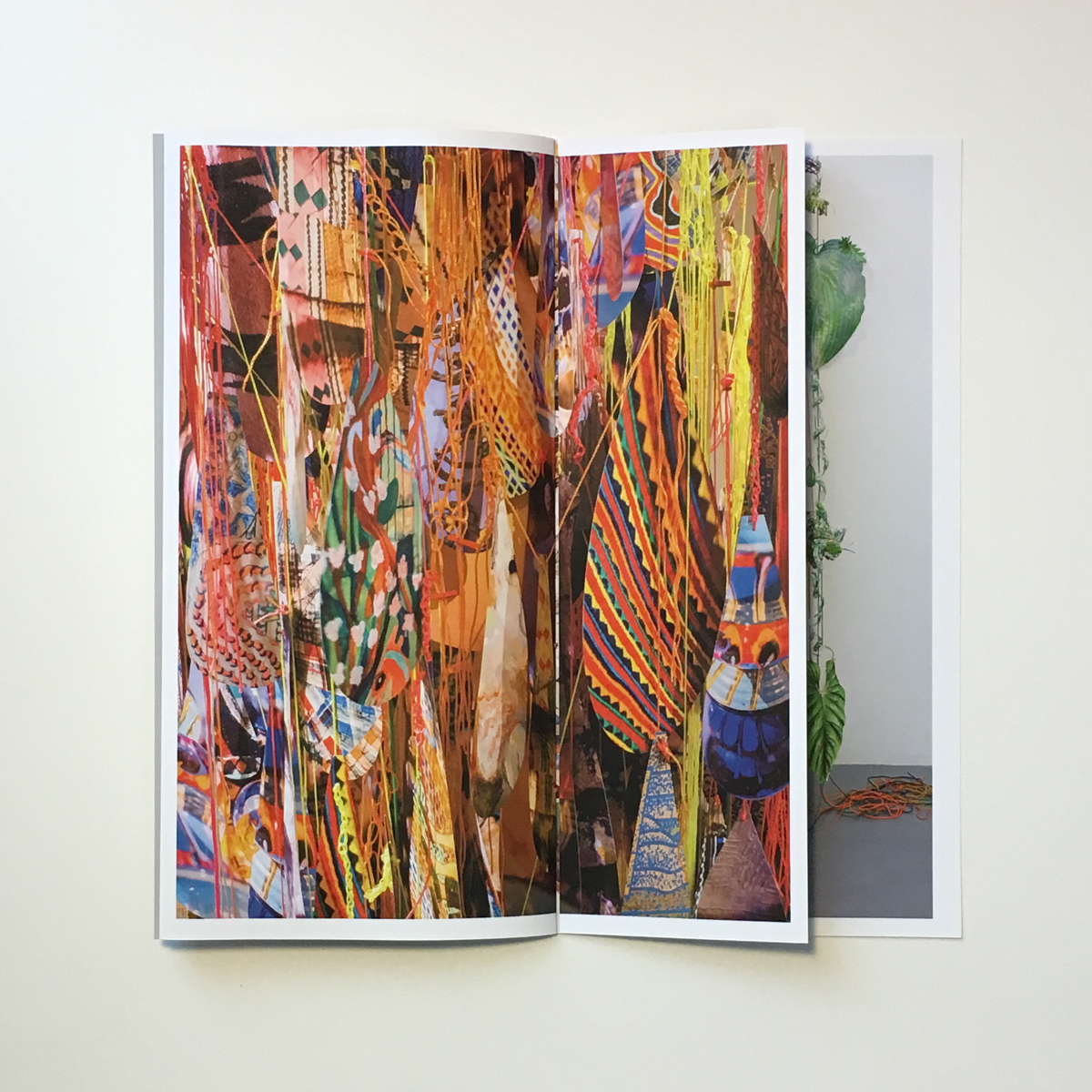

All of the photographs contained within Gusts in the Hothouse were taken in my garden, my mother’s garden, and public gardens near my home in Chicago and my parent’s home in Florida. Lately I have been reflecting on gardens as places where taxonomies and aesthetics intersect with unpredictable elements: as spaces defined by interactions of order, disorder, and temporality. My recent work has been focused on gardens as collections that are ephemeral, evolutionary, and seasonal. In gardens, interconnected systems grow and reproduce. Hybrids flourish. Gardens are portrayals of time. They are marked by seasonality; by various internal cycles of life moving at different speeds: interdependent systems blooming, growing, intertwining, and dying. They represent a kind of inertia toward disorder: our post-apocalyptic visions always feature cities overgrown, being consumed again by nature. I use the garden as a framework to explore the complex attachments formed, individually and institutionally, for what we collect: the tangible and the intangible.

study for Gusts in the Hothouse

Gusts in the Hothouse, 2016

photographs, paracord, grow lights, oscillating fan

Aimée Beaubien’s photographic practice takes shape in inventive forms. Responses to color, pattern, space, structure, time and place are translated from her printed photographs into sculptural interventions. Gusts in the Hothouse meditates on the garden as a space defined by interactions of order, disorder, and temporality. Gardens are collections and conveyors of time from the evolutionary to the ephemeral. They are marked by seasonality; by various internal cycles of life moving at different speeds. Interdependent systems multiply, bloom, grow, intertwine, and die. Gardens are nature gathered together; immaculately tended or grown wild; public space or private refuge. These botanical entanglements provoke a series of experiential shifts between visual representation and physical encounter: leaning, shooting, bedded, staked, staying. Drooping, reclining, pitched, and placed. Sloping, jutting, braced. Holding, heaped. Planted and spread.

Where Art Meets Fashion

studio install of Collecting Within

summer studio

in the studio

Upcoming collaborative installation at The Whistler

studio view

experiments with book forms

PAPER POSITIONS at Bikini Berlin from April 28 - May 14, 2016

Materiality and the Layered (eye)

Materiality and the Layered (eye)

Curated by Marilyn Propp

April 24 – May 29, 2016

Each of the artists chosen by curator Marilyn Propp utilizes the transformative power of collage, an accumulation of material and appropriated and altered imagery, to create juxtapositions and layers of meaning and experience. Phyllis Bramson, Aimee Beaubien, Sandra Perlow, Miriam Schaer, and Douglas Stapleton create works that are densely layered and built, with suggestive narratives or embellished abstraction, and each references the body in his/her work, invoking myth, memory and the pleasure of the material. They present the viewer with their personal vision: intimations of pleasure and the fullness of life, of the darker sides of our human experience, or of social and political implications of gender.

Opening Reception

Sunday, April 24, 2016, 1-4 pm

Artist Panel

The Layered (eye): Materiality and Transformation

Sunday, May 1, 1 – 3pm

Lecture with curator Marilyn Propp

The History of Collage as Social, Political, and Personal Expression

Thursday, May 26, 7 – 8pm.

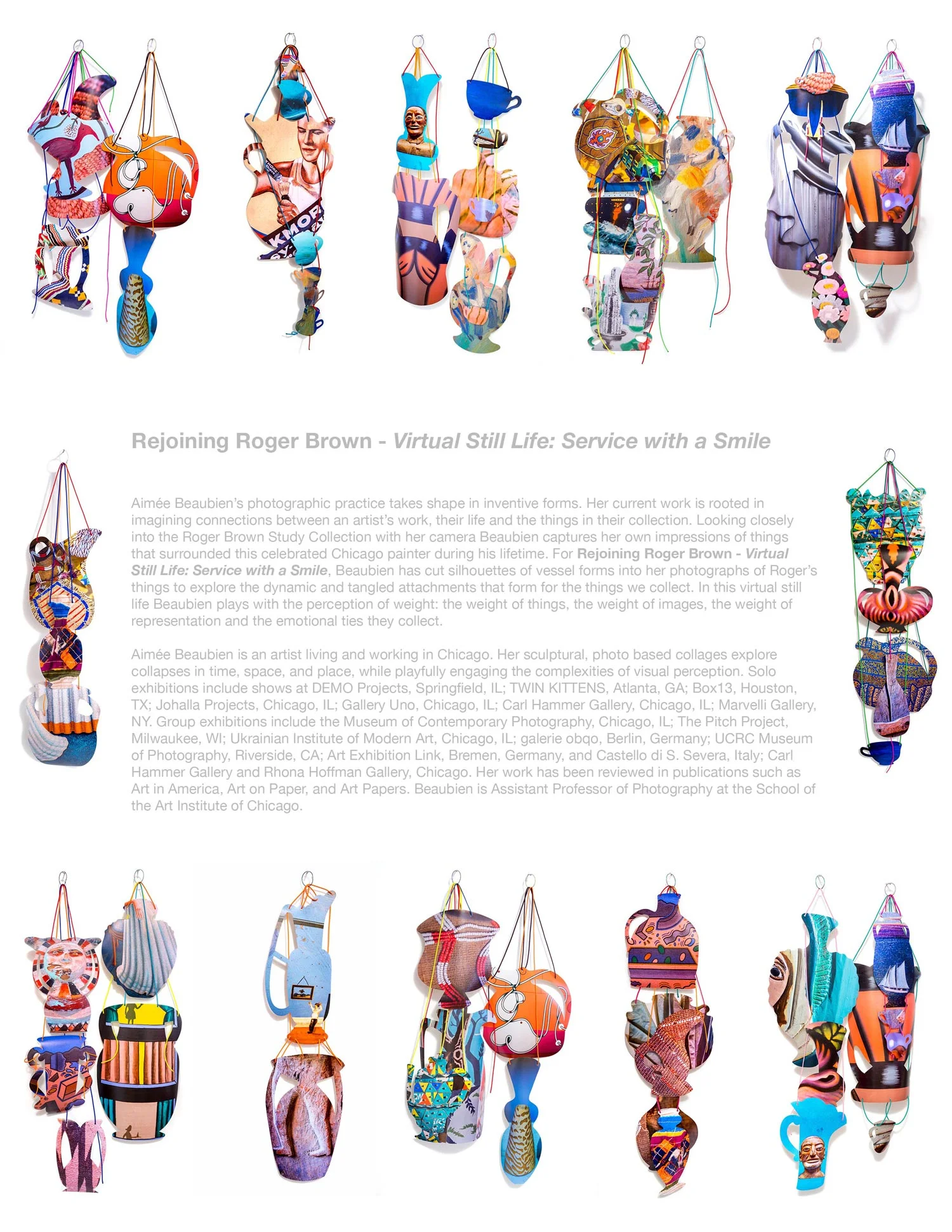

Rejoining Roger Brown - Virtual Still Life: Service with a Smile

OPENING RECEPTION: Monday, April 11th from 5:30 to 7pm

Sixth Floor Millennium Room

University Club of Chicago | 76 East Monroe Street | Chicago, IL

Dress code is business casual – no jeans permitted

Aimée Beaubien’s photographic practice takes shape in inventive forms. Her current work is rooted in imagining connections between an artist’s work, their life and the things in their collection. Beaubien is looking closely into the Roger Brown Study Collection with her camera to capture her own impressions of things that surrounded this celebrated Chicago painter during his lifetime. Beaubien has cut silhouettes of vessel forms into her photographs of Roger’s things to explore the dynamic and tangled attachments that form for the things we collect. In this virtual still life Beaubien plays with the perception of weight: the weight of things, the weight of images, the weight of representation and the emotional ties they collect.

Aimée Beaubien is an artist living and working in Chicago. Her sculptural, photo based collages explore collapses in time, space, and place, while playfully engaging the complexities of visual perception. Solo exhibitions include shows at DEMO Projects, Springfield, IL; TWIN KITTENS, Atlanta, GA; Box13, Houston, TX; Johalla Projects, Chicago, IL; Gallery Uno, Chicago, IL; Carl Hammer Gallery, Chicago, IL; Marvelli Gallery, NY. Group exhibitions include the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; The Pitch Project, Milwaukee, WI; Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, Chicago, IL; galerie obqo, Berlin, Germany; UCRC Museum of Photography, Riverside, CA; Art Exhibition Link, Bremen, Germany, and Castello di S. Severa, Italy; Carl Hammer Gallery and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago. Her work has been reviewed in publications such as Art in America, Art on Paper, and Art Papers. Beaubien is Assistant Professor of Photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

COLLECTING WITHIN AND RECENT WORKS

You’ve been investigating and working with collage since the early 1990s (perhaps earlier?). What prompted you to focus your aesthetic efforts upon this type of art practice? Are there any specific early experiences that prompted a shift away from traditional photography approaches?

I cut photographs up as soon as I began making photographs in the mid-80’s and explored alternative forms of presentation. By cutting into and distorting recognizable formats and materials I had hoped to draw attention to the construction of the image. My great-grandmother introduced me to photography and collage at a very young age. She took photographs everyday with a particular focus on the changing conditions in her garden throughout the seasons and years. The many ways she used her camera to look closely and to hold on to ephemeral matter continues to loom large in my imagination. She had a magical way of repurposing available stuff and employing sophisticated self-taught collage techniques to revitalize material. And as a young art student I was, and continue to be, very excited by artists using photography in unconventional ways. I studied with amazing professors at SAIC (Angela Kelly, Silvia Malagrino, Karen Savage, Barbara Crane) who encouraged experimentation with photography.

Lets jump into your current installation at the MoCP (Museum of Contemporary Photography). This is clearly an ambitious piece that was made specifically to coincide with the celebration of the museum’s 40th anniversary. Can you share with us an introduction to the process and intent?

When I was invited to construct a site-specific installation at MoCP I had just started photographing in the Roger Brown Study Collection. Allison Grant, Assistant Curator, shared some of the plans for MoCP at 40. I wanted to mirror some of the activity in the galleries leading up to the stairwell so I began by thinking about how I could respond directly to the idea of a collection. I find our impulses to collect and what we collect fascinating. Inspired by William Henry Fox Talbot’s early photographs of collections – I took his image ‘Articles of China’ from the 1840’s as a jumping off point to build a wild china cabinet, a suspended cabinet of wonder. Details of my photos, copies of Talbots and my great-grandmother’s climb the stairs informed by familiar memories of following the lives of families in pictures while walking up the staircases in their homes. I treated overlapping collections of photographs in radically different ways inside of this installation – cut, woven, suspended, and transformed. I incorporated two of my personal collections possessing significant emotional meaning to me – the many whiskey jugs my husband makes and my great-grandmother’s photographic archive – and blended my collections with my responses to Roger Brown’s collections. I cut silhouettes of vessel forms into my photographs of Roger’s things and suspended them from brightly colored paracord to hang in layers within an architectural niche 11 feet long by 9 feet high and 3 feet deep. Through Collecting Within I explore the dynamic and tangled attachments that form for the things we collect. And throughout this installation I play with the perception of weight: the weight of things, the weight of images, the weight of representation and the emotional ties they collect.

In looking at the development and history of your work, I see a shift in your approach and the visual elements presented. For instance, there appears to be a progression away from a 2-Dimensional fixed design to a more fluid 3-Dimensional sculptural arrangement. In addition, there appears to be a deterioration of recognizable imagery. Can you share with us your views in how your art practice has progressed over time?

In the past two years my collage gestures have grown into three dimensional sculpture and site-specific installations. I weave visual impressions together and use photographic paper as the primary material to explore physical and perceptual relationships. My depictions of a dimensional world rendered flat in prints reach extended expressions that bulge, hang, weave, and tangle.

I continue to reflect on Geoffrey Batchen’s observations of William Henry Fox Talbot’s ‘Honeysuckle’ c. 1844: “Talbot crowds his camera into the bush of flowering honeysuckle, resulting in a remarkably three-dimensional picture. Looking at this image, we feel as though we too are peering into these branches, our field of vision totally filled by its light-dappled petals and stems. The photograph is at once realist and abstract, and thus points to a paradoxical aspect of photographic vision that many future practitioners would also learn to exploit.”

Transitions in my working process in turn change the ways that I capture moments from my everyday. How much can I cut away? What will agitate associations? As moments drift I crowd in with my camera to draw connections through different conditions in a manner that I imagine information travels through systems and bodies. The act of replacing a complete image in the process of inventing a new one seems analogous to the ways that I process information and reconstruct memories. I think I know something but that thing and my relationship to it continues to transform.

What do you value most in your art practice?

I value working in an exploratory manner. I place myself somewhere not entirely familiar and crowded inside situations where I learn as I go. Photography is always changing and my relationship to it continues to change. I embrace the multifarious nature of photography and the various tangled complications accompanying this medium.

You’re also an educator. Do you have any ongoing philosophies or practices that you try to share with your students? Does you teaching have any specific impact upon your ongoing investigations?

The classroom is an exciting and dynamic environment. I share my enthusiasm for learning and more specifically for learning about the lives of artists and the work they make. I try to get everyone to dance with me on the first day of class. It is embarrassing to dance in front of people but each time I have to remind myself that I feel really connected to what I’m making when I feel vulnerable and not entirely sure of where things are headed. I’ve had some of the most inspiring and revelatory experiences with students when we have allowed ourselves to be open, vulnerable, and generous in our discussions. I encourage people to follow their curiosities, to learn how to push themselves a little harder, to try something new, and to keep on going!

In the past year, you have produced a number of site-specific works that are remarkable in consideration of the labor-intensive side of your practice. So, what’s up next? Are you scheduled for any future projects? Exhibitions?

Thank you! It has been a busy year but I have learned so much from having this series of opportunities to create site-specific installations. My approach to building installations seems similar to how I treat my tiny backyard garden. My garden and an exhibition space are large-scale canvases to explore the potentials of wild compositions. In every way that I engage with my work I seem to naturally gravitate towards building things that require a great deal of labor and attention to detail. Right now I am still generating work in response to Roger Brown’s collection. I am installing a freestanding photo-based sculptural piece in the Roger Brown Study Collection later today and am looking forward to seeing my photos of things in the collection within this home museum. While testing new ways to work with my photographs I continue to imagine connections between an artist’s works, their life and the things they collect.